Aiden Parente

Iron is a redox active metal that is found in the 2+ and 3+ oxidation states in human tissues. Though the toxic effects of iron overload have been well characterized due to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that hemochromatosis (iron overload) can cause. More recently an iron-mediated, pre-programmed, cell death pathway has been found to govern many physiological processes such as cell metabolism and proliferation. This pathway, ferroptosis, involves the accumulation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) that eventually result in uncontrolled lipid peroxidation and degradation of the membranes necessary for cell survival.

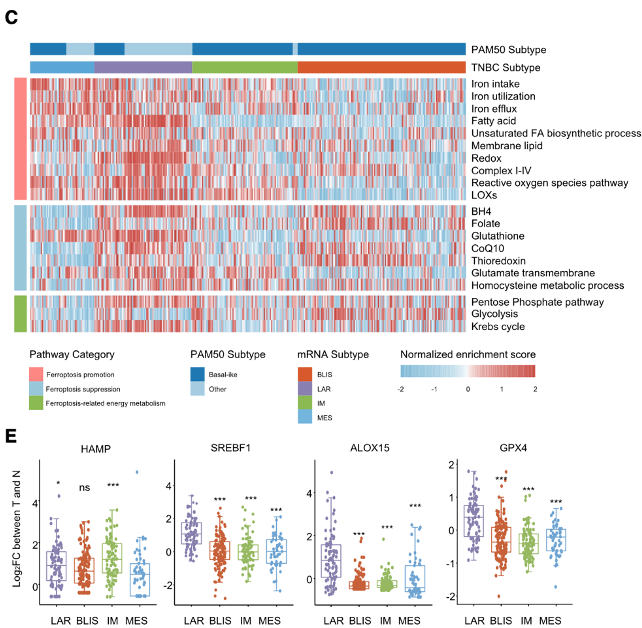

The first paper by Yang et al. demonstrates the heterogeneity of ferroptosis in different subtypes of triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) and uses the information gained from their multiomics approach to show the efficacy of novel treatments for TNBC that combines immunotherapy with small molecule inhibitors. First, Yang et al. defines the main subtypes of TNBC that have varying susceptibility to drug-induced ferroptosis: mesenchymal-like (MES), luminal androgen receptor (LAR), immunomodulatory (IM), and basal-like and immune-suppressed (BLIS). Based on the enrichment scores of ferroptosis associated proteins in single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA), LAR tumors had higher levels of fatty acid metabolism, as well as greater production of reactive oxygen species, making LAR tumors especially susceptible to drug-induced ferroptosis.

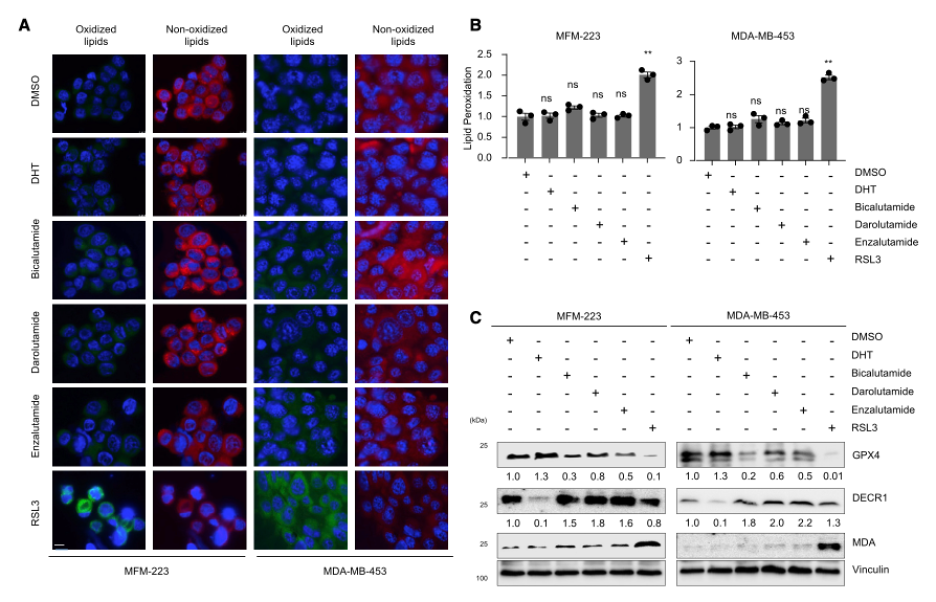

Based on the proposed susceptibility of LAR tumors to ferroptosis induction, Yang et al. explored the efficacy of drug-induced ferroptosis in LAR tumors and the relationship between ferroptosis and the androgen receptor (AR) to find target proteins in this pathway for novel therapeutics. Because AR simultaneously downregulates and upregulates ferroptosis suppressors like DECR1 and GPX4 respectively, the androgen receptor is not a viable drug target, and its inhibition did not effectively induce ferroptosis in MFM-223 and MDA-MB-453 cells.

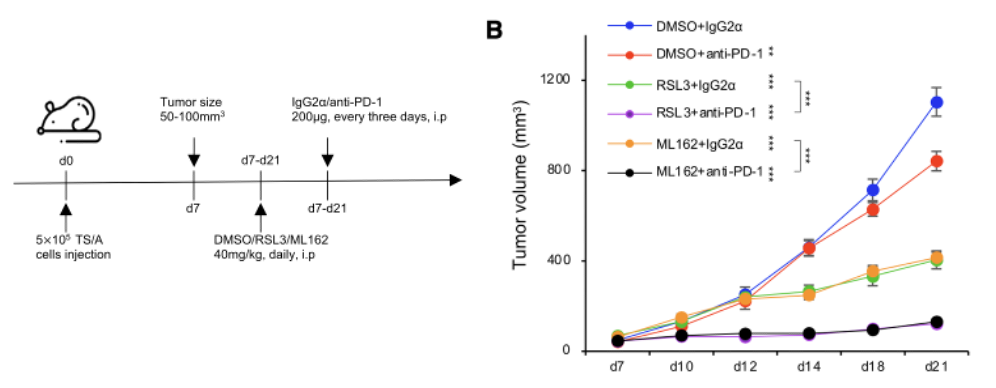

Thus, the inhibition of GPX4 with RSL3 and ML162 was evaluated in tissue culture and mouse xenograft models to see the effects on the tumor microenvironment and tumor growth. Interestingly, it was noted that inhibition of GPX4 resulted in enhanced recruitment of immune cells that can detect and kill tumor cells (CD3e+, CD4+, CD8+, and CD86+) and decreased the presence of tissue repair and angiogenesis inducing M2- macrophages that promote tumor growth. Thus, the researchers hypothesized that GPX4 inhibition may be a promising combinatorial therapy with immune checkpoint blockade therapy (ICB), which helps the body’s immune system recognize and fight tumor cells. The efficacy of this treatment was demonstrated in mouse xenograft models by measuring the effects of RSL3 and ML162 treatment with PD-1 and G2α antibodies, where the ICB therapy anti-PD-1 resulted in a significantly reduced tumor volume in combination with RSL3 and ML162.

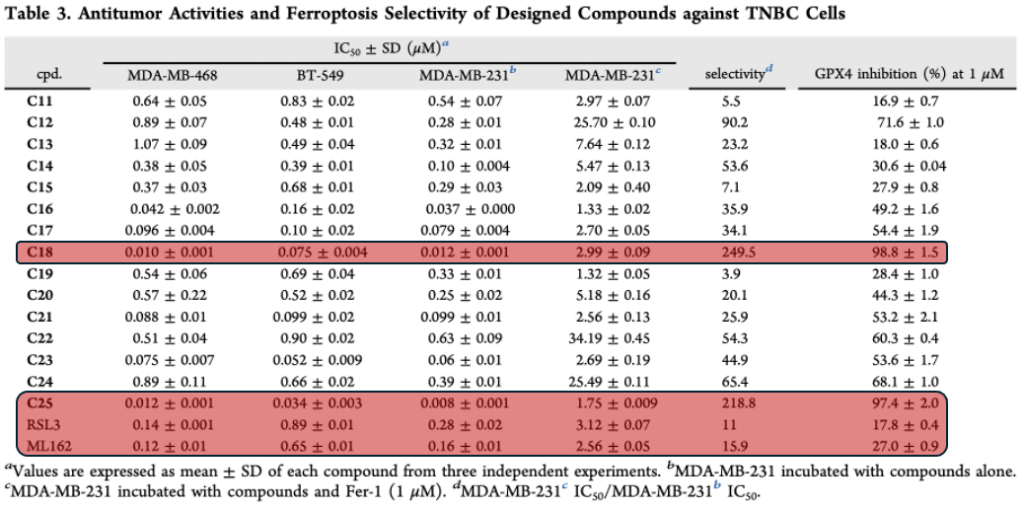

The second paper compliments the research done by Yang et al. by evaluating the development of novel GPX4 inhibitors that use the same irreversible inhibition mechanism as RSL3 and ML162. Novel inhibitors of GPX4 that Chen et al. evaluate all contain the highly electrophilic α-chloro-amide moiety that reacts with sec46 in GPX4 to inhibit it irreversibly. But, to improve the efficacy of this class of GPX4 inhibitors, Chen et al. reduced the conformational flexibility and size of the compounds so they could better fit in the GPX4 binding pocket. This resulted in the development of compounds C18 and C25, which showed much better inhibition of GPX4 and selectivity for ferroptosis when compared with RSL3 and ML162.

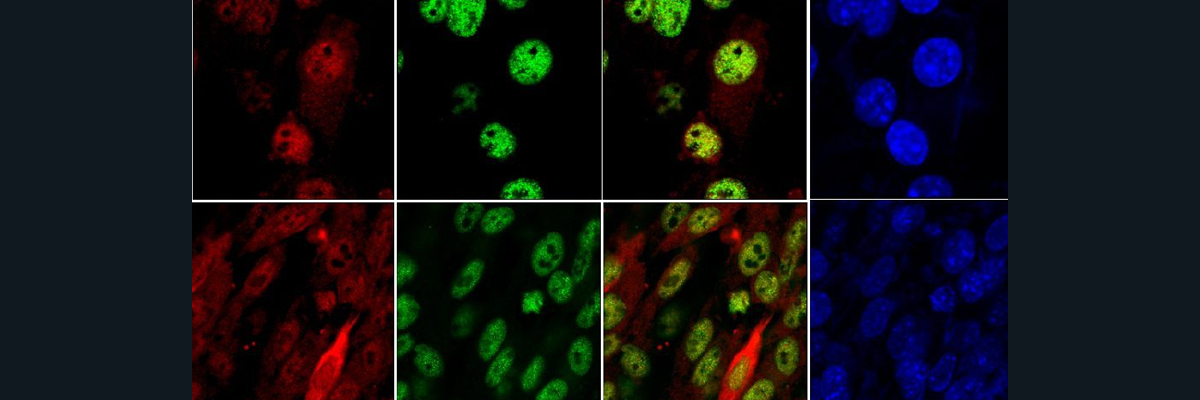

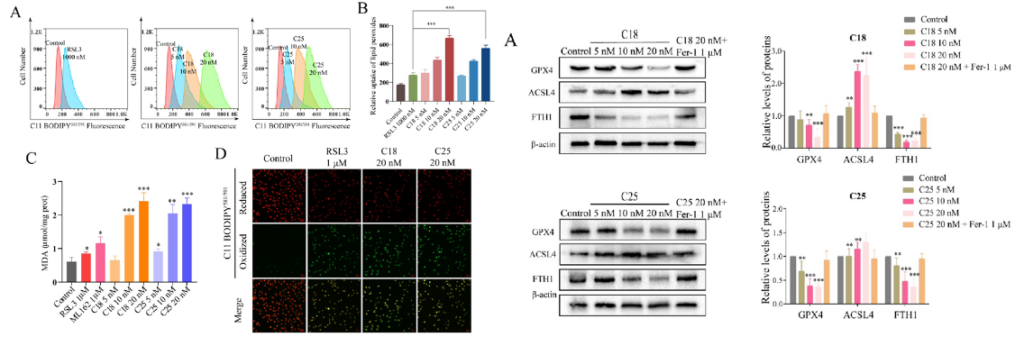

The effectiveness of C18 and C25 induced ferroptosis was compared to that of RSL3 and ML162 in MDA-MB-231 cells by measuring the accumulation of malondialdehyde (MDA), which is a metabolite of lipid peroxidation. The accumulation of MDA along with the reduction of negative ferroptosis regulatory proteins indicated that C18 and C25 successfully induced ferroptosis in a concentration dependent manner.

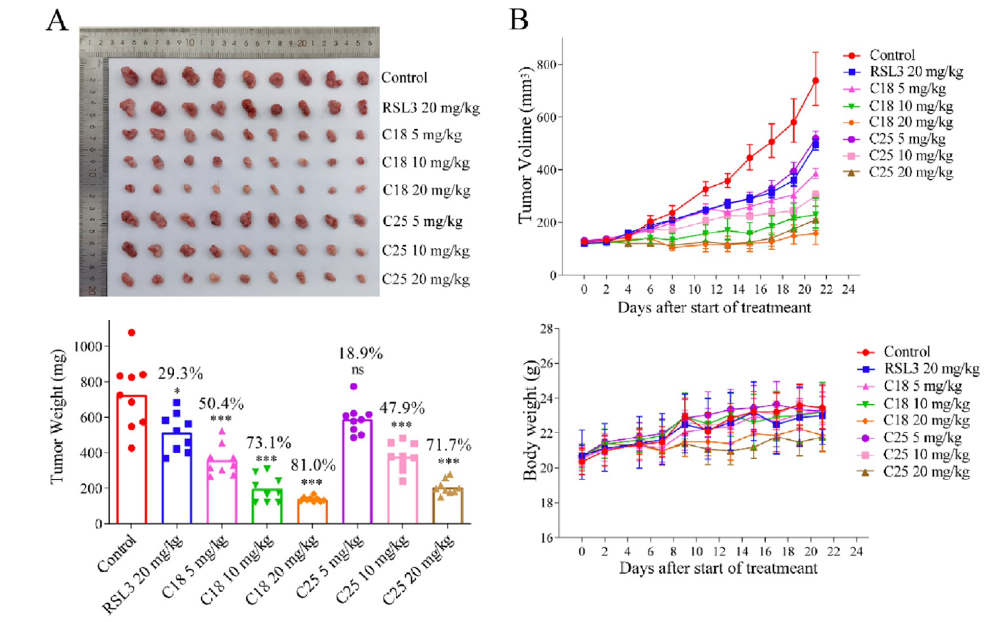

The efficacy of C18 and C25 for TNBC treatment was also evaluated with a mouse MDA-MB-231 xenograft model by characterizing the change in tumor size, weight, and presence of proliferation markers like Ki67. C18 and C25 showed much higher inhibition of tumor growth at significantly lower concentrations than RSL3 and ML162 with daily intraperitoneal injections for 21 days.

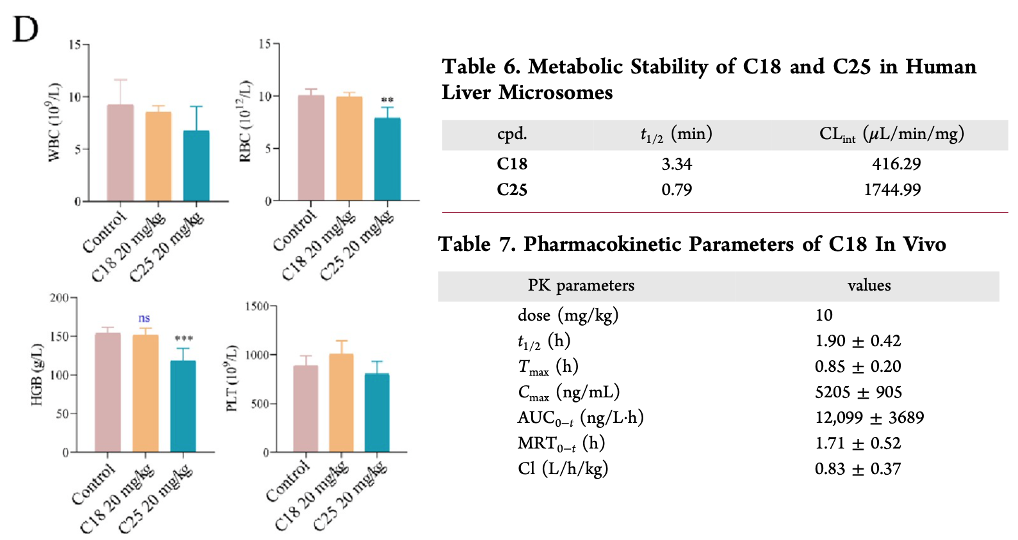

C18 and C25 successfully limited tumor growth at a dose of 20 mg/kg. Though in pharmacokinetic analysis, C25 did show characteristics of bone marrow toxicity based on the decrease white blood cell, red blood cell, and hemoglobin count present in the blood stream. Moreover, C18 had more favorable pharmacokinetic parameters, better stability in the liver, and a longer half-life in vivo. Thus, C18 is a promising covalent inhibitor of GPX4 that could be effective in treatment of TNBC, and may also have synergistic effects with immunotherapy, as described by Yang et al. Both studies demonstrate how a combined genomic and proteomic approach to treatment has helped researchers design more personalized and selective drugs that target iron homeostasis mechanisms in tumors.

References:

(1) Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2021;22(4):266-82. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8.

(2) Yang F, Xiao Y, Ding J-H, Jin X, Ma D, Li D-Q, Shi J-X, Huang W, Wang Y-P, Jiang Y-Z, Shao Z-M. Ferroptosis heterogeneity in triple-negative breast cancer reveals an innovative immunotherapy combination strategy. Cell Metabolism. 2023;35(1):84-100.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.021.

(3) Tingting Chen JL, Jun Tan, Yongjun Zhao, Shanshan Xie, Shifang Zhao, Xiangyu Yan, Liqiao Zhu, Jun Luo, Lingyi, Kong, Yong Yin. Discovery of Novel Potent Covalent Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Inhibitors as Highly Selective Ferroptosis Inducers for the Treatment of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2023;66(14).