Type 1 Gaucher Disease is an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disease, as both copies of the gene must be defective. Carriers have one normal and one defective gene. It is caused by missing the enzyme β-glucocerebrosidase that breaks down a glycolipid called glucocerebroside, which accumulates in the body. Symptoms can come up at any age and can include the following: enlargement of the spleen/liver, easy bleeding/bruising, fatigue, weak bones, as well as bone and joint pain.

Historically, there have been several reports of Gaucher patients having hyperferritinemia (serum ferritin 2-3x of the normal); this means that there could be an altered iron homeostasis pathogenesis in Gaucher Disease. Ferritin stores iron, but serum ferritin could rise with tissue inflammation. Iron is typically stored in the spleen and liver, regulated by hepcidin, a hormone that reduces iron release. Hepcidin blocks ferroportin (an iron exporter), so that iron cannot leave and stays in the cell. Hepcidin levels increase with inflammation, which raises ferritin levels and reduces iron availability, causing anemia.

One method the researchers used was Perl’s Staining: In Perls’ Prussian Blue (PPB) stain for iron, Fe3+ is released from treatment with HCl; the metal reacts with potassium ferrocyanide to form ferric ferrocyanide, a bright blue pigment. As seen in the figure below, A is a medullary smear, and B is spleen sections. Large, stained cells are Gaucher cells that are showing iron deposition

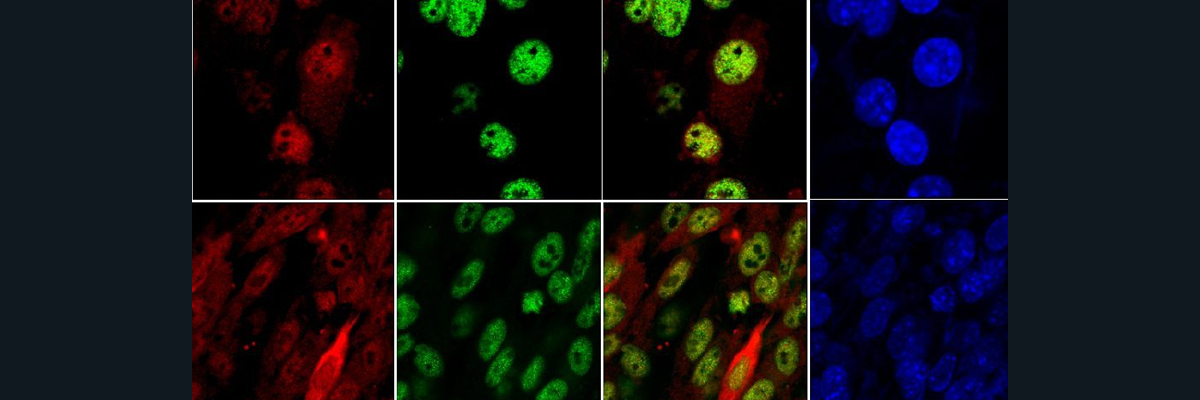

Furthermore, The researchers created a Gaucher like phenotype in lab grown macrophages (J774 cells), by using CBE to inhibit glucocerebrosidase. Figure A: in CBE untreated cells, the FPN (iron exporter) is very pronounced (bright green pigments), indicating iron being exported at high levels. In CBE treated cells (glucocerebrosidase inhibitor), FPN levels drop significantly (less bright green pigments), indicating iron accumulation. Figure B: FPN mRNA levels increased when glucocerebrosidase was inhibited, suggesting FPN downregulation is post-translational. Figure C: Hepcidin mRNA levels increase with +CBE. This makes sense suggesting that iron isn’t being exported and accumulating. This means that hepcidin production may play a role in reducing FPN levels via an autocrine/paracrine mechanism. Figure D: in +CBE cells, ferritin level % increases, suggesting iron accumulation.

A longitudinal study showed that biological abnormalities improve from ERT, confirming the local iron sequestration hypothesis. The researchers were looking to compare how ERT responses differ with age. As seen in the graphs below, Patient 1 is an 18 year old woman, whereas patient 2 is a 52 year old woman, both who just started ERT. Patient 1 has a much quicker response (ferritin levels decrease more rapidly), suggesting that younger patients are more likely to see improvements at a faster rate. More data is needed to confirm that younger patients have a quicker response, as this is just one example of a young and older woman. In Figure C, it is seen that in untreated patients, there is no regulation of increased ferritin with iron storage (hepcidin), as seen with relatively less correlation between ferritin and hepcidin. In treated patients, as ferritin levels rise, there is an increase of hepcidin. This is seen with the stronger correlation between ferritin and hepcidin. This is likely to regain a balanced iron status, and control the iron excess from the improvement of iron release in Gaucher cells.

In conclusion, Hyperferritinemia in type 1 Gaucher Disease patients is related to abnormal iron metabolism and iron sequestration in Gaucher cells. ERT releases the iron, improves iron status, and corrects the anemia. Hyperferritinemia occurs in Gaucher cells because of the downregulation of the iron exporter ferroportin. Hepcidin from the macrophages is responsible for the ferroportin repression. These results offer new perspectives for treatment of Gaucher Disease. Whether hepcidin is induced by a local inflammatory state or directly from lipid mediated pathways is still unknown.

Sources:

Lefebvre, Thibaud, et al. “Involvement of Hepcidin in Iron Metabolism Dysregulation in Gaucher Disease.” Haematologica, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Apr. 2018, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5865418/.